Share this

High and Growing Dividends

by Kevin Malone on Jun 22, 2023

Perception is reality... Or is it? When many individuals think about dividend-oriented equity investment strategy, a prototypical investor comes to mind. One who is conservative and relatively risk averse; one who seeks value stocks and desires income as a primary objective. Well, such an investor could greatly benefit from a well‐structured portfolio of attractive dividend paying stocks; however, so could many others including those investors with a more aggressive style in mind. In reality, stocks that pay high and growing dividends can serve as the basis for an intelligent and viable core strategy for any equity portfolio, regardless of the investor’s return objectives and tolerance for risk.

A Historical Perspective

The S&P 500 started in 1958, and since then 33% of the total returns of domestic common stocks have been attributed to dividends with the other 67% coming from capital appreciation. In other words, with a long‐term return on common stock of about 10%, one third was derived from dividends. While many investors are initially surprised at the impact that dividends have had on the equity markets as a whole, they quickly point out that 50 years ago represented a very different age in investing. Large‐capitalization companies dominated the equity markets and investors primarily consisted of the “rich and famous” who expected to see some immediate return on their investments in the form of cashflow. The most successful companies were those that were able to return nice dividends to their affluent shareholders.

Narrowing the time frame actually delivers some very surprising (and favorable) results. Since the 1980s, more individuals have begun participating in the equity markets; the popularity of retirement accounts and company‐sponsored plans brought an entirely new generation of investor. While current income remained a key objective

for a good number of them, many focused more on capital appreciation as they attempted to build that nest egg for retirement. The emphasis on dividends (seemingly) became less important and corporate management often chose to reinvest directly back into their companies instead of paying out profits to shareholders on a periodic basis. In fact, some analysts and investors alike went so far as to mock those companies that paid dividends. Apparently, they became a symbol of management’s lack of foresight and/or creativity when it came to spending or reinvesting the company’s excess cashflow. Even with this larger playing field, dividend paying stocks were generally perceived to be most appropriate for value investors seeking current income.

The Numbers Don't Lie

Since 1958 a hypothetical dividend-oriented portfolio consisting of the top 20% of S&P 500 index companies ranked by dividend yield and weighted by capitalization has outperformed the overall benchmark S&P 500 index by 158 basis points or 1.58% per year. During that period, the dividend portfolio earned a 12.59% compounded annual return compared to 11.02% for the S&P 500 index. The return assumes that the portfolio was rebalanced annually to account for any changes among the top 20% of dividend yielding stocks within the index and also assumes that all dividends are reinvested. See appendix.

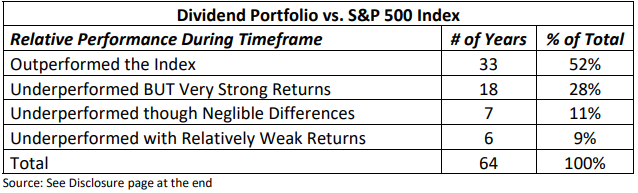

For those 64 years, the dividend portfolio outperformed the index on 33 occasions or 52% of the time. Delving deep inside the numbers reveals that even in certain years when the index beats the portfolio, the dividend strategy still performed quite well. During 18 of the 64 years, the portfolio underperformed the index but still rewarded investors with at least a 9% return while incurring far less risk than most growth-oriented portfolios. In fact, during those 17 years, an investor in that dividend portfolio would have earned an average return of 16.0%. In 7 of the 64 years, the dividend portfolio returned less than the S&P, though the differences actually could be considered quite negligible. Only in 6 of the 64 years, did the dividend portfolio significantly under‐perform the S&P 500 while returning relatively weak results. All in all, the performances of the dividend portfolio over a substantial 64‐year timeframe were quite favorable, both on an absolute and relative basis.

Peace of Mind During Market Downturns

Most investors understand that cashflow helps provide a cushion during periods of declining markets; companies that generate free cashflow and pay out dividends typically are less volatile and perform better during these times. While some of these stocks still may fall as the overall markets fall, the dividends provide cashflow benefits to the investors. For example, since 1926 the average total return of the U.S. Common Stock index during declining years was ‐13.24% per year, while the average return from the dividends portion alone was +3.59% during these same periods. Therefore, the dividend oriented portfolio generated a cashflow return of about 1% per quarter, a cushion that helped many investors sleep better at night during those bearish times.

Characteristics of a Dividend Paying Company

Historically, management’s decision to pay (or increase) dividends has indicated a strong commitment to its shareholder and has been reflective of the underlying company’s overall financial strength. Investors sought out those solid companies that generated free cashflow, which in turn they passed along to their shareholders. Utilities, financials, and consumer staples were among the most likely industry sectors from which companies paid dividends, but that may be changing as we now see companies in all sectors paying dividends. Growth companies like those within the technology sector often reinvested any profits earned in lieu of sharing with investors in the form of dividends. Until 2003, dividends were taxed at ordinary income rates and many investors believed that such reinvestments led to greater capital appreciation potential, a benefit to them because the capital gains tax rate was far lower. Under the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003, the tax rate on dividends was reduced to 15% (same as long‐term capital gains) and suddenly more investors desired dividend paying stocks. Microsoft is an example of one technology company that did not pay dividends, but changed its policy for the benefit of its shareholders.

Portfolio Construction

The dividend oriented portfolio can be structured either using a passive or active management philosophy. An investor can create a core portfolio of stocks using the 100 highest yielding stocks from the S&P 500, reinvest the dividends, and rebalance each year as changes to the index are made. As described above, such a portfolio has outperformed the benchmark by an average of 158 bps (1.58%) annually since 1958. See appendix

On the other hand, an actively managed portfolio that adherers to a similar strategy has the potential to perform even better. Rather than remain restricted to the highest yielding S&P stocks, the experienced manager can structure a well-diversified core portfolio that consists of growth and value, large-, mid-, and small-capitalization, and U.S. and international companies which pay attractive dividends.

While it seems obvious that higher yielding stocks have higher than average dividends, the current yields on portfolios vary over time. The investment managers we choose for portfolios have also focused on companies that have a tendency to raise dividends. The combination of higher yields and growth of dividends have meant these portfolios have a lower dependency on price appreciation. Therefore, we believe such a core actively‐managed portfolio can provide strong cash flow with a reasonable tax liability, offer excellent appreciation potential, and cushion the investor against a downturn in the market.

Current Considerations

Many uncertainties remain in the current market environment. A weak housing sector and global debt issues threaten the overall strength of the economy. On the other hand, corporate earnings have continued to grow, quarter after quarter. Given the favorable tax treatment, management has incentive to reward its shareholders with excess cashflow in the form of dividends. And the results speak for themselves. A core portfolio that pays high and growing dividends can prove effective in both rising and declining markets for investors of all shapes and sizes (or rather return objectives and tolerances for risk)….regardless of traditional perception.

Disclosure

Unless otherwise indicated, S&P 500 historical price/earnings data herein is from www.standardandpoors.com, SP500EPSEST.xls. S&P 500 and S&P Top 100 by dividend yield historical return data provided by Siegel, Jeremy, Future for Investors (2005), With Updates to 2020. Each stock in S&P 500 is ranked from highest to lowest by dividend yield on December 31st of every year and placed into “quintiles,” baskets of 100 stocks in each basket. The stocks in the quintiles are weighted by their market capitalization. The dividend yield is defined as each stock’s annual dividends per share divided by its stock price as of December 31st of that year. References to “returns” refer to the total rates of return compounded annually for periods greater than one year, with dividends reinvested on the S&P as a whole, or on the Model, as applicable, for the period of time (years) indicated. As such, “returns” are a measure of gross market performance, not the performance of any client’s investment portfolio (which would ordinarily be subject to management fees and, possibly, custodian fees and other expenses).

Share this

- November 2025 (1)

- October 2025 (1)

- September 2025 (1)

- August 2025 (1)

- July 2025 (1)

- May 2024 (2)

- April 2024 (2)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (1)

- January 2024 (2)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (1)

- October 2023 (1)

- August 2023 (1)

- July 2023 (3)

- June 2023 (4)

- May 2023 (1)

- April 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- February 2023 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

.png?width=2167&height=417&name=Greenrock-Logo%20(1).png)